Citizen DJ is officially open to the public and all sounds on this website are completely free-to-use for your remixing needs. Read a behind-the-scenes retrospective post on this experimental project and residency.

Citizen DJ 2020 Retrospective

The following is a end-of-residency retrospective post by Brian Foo, 2020 Innovator in Residence and creator of Citizen DJ.

In July of 1945, the world was in the midst of war and New York City was in the midst of a newspaper delivery strike. Despite being largely pro-union in his policies, then New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia made a political statement by reading comic strips such as Little Orphan Annie and Dick Tracy over the radio. This moment would become one of the most historical and memorable uses of the medium. So much so, the Library of Congress inducted this recording into the National Recording Registry in 2007, an honor reserved to only 25 recordings each year.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia reading comic strips over the radio in 1945. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia reading comic strips over the radio in 1945. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Forty years later in 1985, hip hop producers Double Dee and Steinski create a track “Lesson 3 — The History of Hip-Hop Mix”, an attempt to survey the history (only about seven years at the time) of breakdancing favorites, while mixing in snippets from speeches and talk shows including LaGuardia’s 1945 readings of the comics. You can hear the sample at the very end, quoting LaGuardia’s perceived moral of a Dick Tracy strip: “Say children, what does it all mean? It means that dirty money never brings any luck!” Four years later in 1989, hip hop group De La Soul released their landmark debut album, 3 Feet High and Rising, which begins with a track “The Magic Number”, a direct reference to Double Dee and Steinski’s “Lesson 3”, also contains many samples including the same LaGuardia quotation, about 22 seconds into the track. In 2010, the Library of Congress inducts 3 Feet High and Rising into the National Recording Registry.

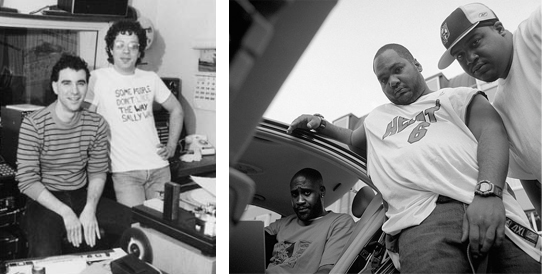

Musical duo Double Dee and Steinski (left) and hip hop group De La Soul (right). Photos courtesy of Library of Congress and Mika Väisänen

Musical duo Double Dee and Steinski (left) and hip hop group De La Soul (right). Photos courtesy of Library of Congress and Mika Väisänen

This is what I love about sampling and this is what I love about hip hop: an artform and culture that weaves together references, quotations, and history into something brand new and culturally significant in its own right. As a listener of hip hop, the sample is a rabbit hole of sonic discovery. It is not unreasonable to ask whether we would be talking about the LaGuardia recording if it was never sampled by Double Dee, Steinski, and De La Soul. The Library even mentions the derivative works in their press release inducting the LaGuardia recording into the Registry.

The art of the sample is also the basis of my one year residency at the Library of Congress and my project, Citizen DJ. This post will attempt to give you a look behind the scenes of my time at the Library and the making of Citizen DJ.

My copyright journey

It’s significant to note that tracks “Lesson 3” by Double Dee and Steinski and “The Magic Number” by De La Soul, together composed of dozens of samples, were created during the so-called “golden age of hip hop.” This was a period of time before copyright law caught up to the hip hop producer, resulting in albums such as It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, 3 Feet High and Rising, and Paul’s Boutique, widely considered masterworks of sonic collages, often composed of dozens of bite-size samples. Following high profile lawsuits in the decade following hip hop’s golden age, collage-based hip hop became largely a lost artform. “Lesson 3” and “The Magic Number” could not be produced under today’s copyright law. And as of this writing, De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising cannot be streamed or downloaded.

The majority of my residency was spent learning about and navigating current copyright law in the context of sample-based music. A lesson I’ve learned over and over again during this time is that this is a very, very complex topic. To illustrate this I will describe an example of audio material that did not make it into Citizen DJ and why. The Southern Mosaic collection represents the three-month, 6,502-mile recording trip through the southern United States in 1939 by John Avery Lomax, Honorary Consultant and Curator of the Archive of American Folk Song (now the American Folklife Center archive), and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax. During this trip they recorded approximately 25 hours of folk music from more than 300 performers, including future Blues Hall of Famer Bukka White and future Alabama Women’s Hall of Famer Vera Hall. This is a massive, rich, and important collection that I encourage you to listen to.

What would it take to sample from Bukka White’s Po’ Boy, recorded in 1939? Field recordings of musical performances often have at least three layers of copyright: the collector, the performer, and the songwriter. In this case, the Lomaxes recorded this on behalf of the Library of Congress, thus their work should be in the public domain. But it’s less clear whether performer Bukka White relinquished his rights to the performance, or even if he did, if it was done so transparently and in good faith. Furthermore, like most blues songs, it is very difficult to track down the original songwriter given the ever-evolving, nonlinear, and oral tradition of blues and folk music.

Audio recording of Po’ Boy by Bukka White

Furthermore, if you dig a little deeper into the Bukka White recording, you’ll learn that it was recorded while White was serving time in Mississippi State Penitentiary, commonly known as Parchman Farm. The Lomaxes often visited prisons as part of their recording trip, and in some cases, created ongoing relationships with inmates. While driving through South Carolina, they were appalled to see a chain gang of approximately 80 prisoners connected by an ankle chain; they recorded the group singing spirituals and work songs, and composed a letter to the governor to protest this “unnecessary and inhuman” practice. The recorded performers were likely not compensated for their musical contributions during their lifetime. It is in my opinion, and also the opinion of the staff of the American Folklife Center, that this context matters when thinking about creative reuse of this material. Does this mean you shouldn’t sample it? Unfortunately there’s no easy answers, just many questions.

We decided very early on that the threshold for inclusion into Citizen DJ in terms of copyright must be very high because we wanted to clearly and definitively say that you can use the source material to make new music, even commercial music, for free and without restriction. This unfortunately excludes collections like The Southern Mosaic collection for the ambiguous copyright-related issues of music performers’ rights. However, we developed a guide to digital sampling to hopefully make it easier to navigate and think about copyright and ethical considerations when digging for sounds outside of Citizen DJ.

We also hope to give Citizen DJ users the tools to dig deeper into the material we reference, perhaps uncovering stories and historical context, like those I found in the Lomaxes’ trip through the American South. Every sound snippet and excerpt you hear on Citizen DJ includes a link to the referenced material’s detail page, information about how you can use it, and some context as to why it is free-to-use.

Despite the challenges and complexities of music copyright, Citizen DJ does not try to simplify, change, or circumvent copyright law. Citizen DJ does try to challenge the public to think critically about the relationship between creativity and access to historical and cultural source material. Citizen DJ does try to remind us that part of the role of copyright law is to encourage the creation of new art and culture. I hope by using Citizen DJ, creators and publishers on both sides of the sampling coin can have more nuanced and practical discussions about how we can use existing cultural material to create new cultural material in a responsible and fruitful way.

Our collective crate of sounds

So what sounds can we use for free? I also asked the Library staff, “What are some sounds that people should know about?” and “What are some sounds that could be compelling building blocks for new music?” To answer this question, with support from LC Labs, I was able to meet incredible staff who work across the Library who have deep knowledge of the Library’s collections.

I feel it’s important to reiterate that the collections that we identified and cleared for reuse represents an immense amount of work by staff across the Library, from collection managers to legal counsel to reference librarians. You can be confident that you can use these in your new (even commercial) works, and that is the direct result of careful research and due diligence done by Library staff on behalf of the public. Here are some highlights:

Like Double Dee and Steinski, you too can remix the iconic voice of Fiorello LaGuardia in the American English Dialect Recordings from the American Folklife Center along with other famous speeches from Eleanor Roosevelt and Amelia Earhart. However, the true gems of this collection are embedded in the hundreds of oral histories collected as part of an effort to document the richness of the American English language and experience. There are Gullah speakers from coastal South Carolina, sharecroppers from Arkansas, Puerto Rican teenagers in New York City, Basque sheepherders from Colorado, Chesapeake Bay watermen, Vietnamese immigrants from Northern Virginia, and many others.

Audio recording of Speech by Fiorello H. La Guardia, New York

In the early 20th century, sound recording technology was transitioning from the wax cylinder to the plastic disc, the predecessor of today’s DJ vinyl record. Thomas Edison, the inventor of the cylinder phonograph debuted his Edison Disc Phonograph in 1911 in response to the changing markets. You can find some of these early disc phonograph recordings in the Inventing Entertainment and Variety Stage collections which span popular music, opera, animal acts, burlesque, dance, and comic sketches. Remix a 1918 vaudeville sketch called “A study of mimicry”, where performers Orren and Drew reproduce a farmyard soundscape using only their voices and “without the aid of any mechanical device whatsoever.”

Audio recording of A study in mimicry : vaudeville sketch

The Joe Smith Collection documents surprisingly candid conversations with hundreds of celebrated musicians and cultural icons including James Brown, Joan Baez, and David Bowie. You can remix a conversation with Bo Diddley where he speaks frankly about his often overlooked role in the birth of rock and roll (16:30) and later (33:00) worries about his and his contemporaries’ legacies.

Audio recording of Off the record interview with Bo Diddley, [1986-1988?]-04-28

Citizen DJ contains contemporary music as well. The Dyann Arthur and Rick Arthur collection of the MusicBox Project documents women roots musicians of all ages and career levels from all over the country. The audio contains a combination of oral histories and live acoustic performances from the past two decades. Remix a performance of Richmond Blues by Eleanor Ellis and Julius Daniels.

Tony Schwartz was an eclectic radio personality and collector of sounds with a career spanning 55 years and a collection of some 30,000 folk songs, poems, conversations, stories and dialects from his surrounding neighborhood and 46 countries around the world. Despite being active before the birth of the hip hop remix, his style was strangely contemporary. Discarding traditional radio formats, Schwartz jumped from sound experiments to sound collages to a mix of old automobile horns which you can remix on Citizen DJ.

Tony Schwartz in the field. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Tony Schwartz in the field. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

The U.S. government is the largest film producer in the United States. And all films created by U.S. government employees as part of their job automatically enter the public domain the moment they are created. The Library’s National Screening Room contains some of those films such as A better America (remix this) documenting WPA projects being carried out on a nation-wide level during the depression. I find it especially meaningful for Citizen DJ, a project made possible by the U.S. government, to include historical creative work that was also made possible by the U.S. government. You can find predecessors to Citizen DJ in the Library’s collections including the WPA Federal Music Project.

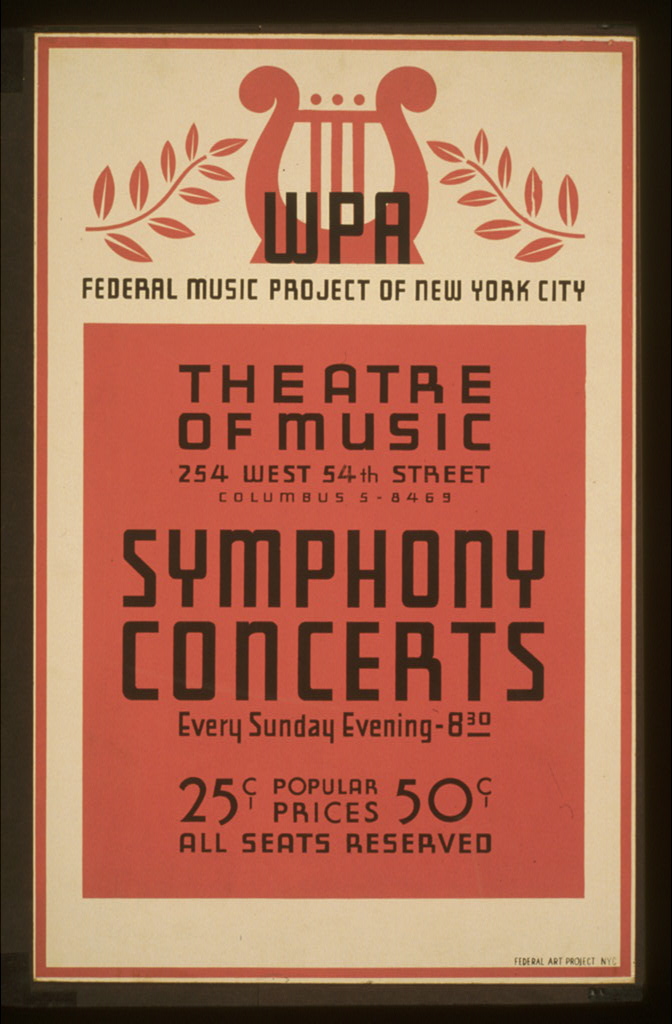

“Symphony concerts WPA Federal Music Project of New York City Theatre of Music.”, a WPA poster created between 1936 and 1941

“Symphony concerts WPA Federal Music Project of New York City Theatre of Music.”, a WPA poster created between 1936 and 1941

Lastly, to add some contemporary sonic diversity to the mix, Citizen DJ also includes public domain material from the Free Music Archive, a website that was devoted to distribution and curation of rights-free music. The Library of Congress archived this website as part of its Web Cultures Web Archive, which includes websites documenting the creation and sharing of emergent cultural traditions on the web. A subset of the archive which represent new works that were dedicated to the public domain by their creators are available on Citizen DJ. Assorted niche genres such as chiptune, freak-folk, and noise-rock are available to remix on Citizen DJ.

Although these collections just scratch the surface of the Library’s audio holdings, I hope they give a sense of the diversity of what the Library has to offer, provide unique source material for your new work, and encourage you to follow the rabbit hole to the Library’s millions of sound recordings and moving images.

Designing for the DJ

In hip hop, there’s a term called “crate digging.” In addition to being alchemists, DJs are also excavationists. Half of their time is spent “digging” for the obscure and the rare sonic gems hidden in a sea of crates in the basements of record shops and thrift stores. The DJ’s reputation and craft are built on how large and diverse their library of sounds are and how adeptly they can recall the right palette of sounds to mix together in the right moment.

The Citizen DJ interface was designed to build on the feeling and function of crate digging. My goal was to make it as easy as possible to discover, listen to, and access large amounts of sounds from a music-making point of view. The first tool I developed was an interface that made it easy to browse thousands of clips within a collection in a matter of seconds.

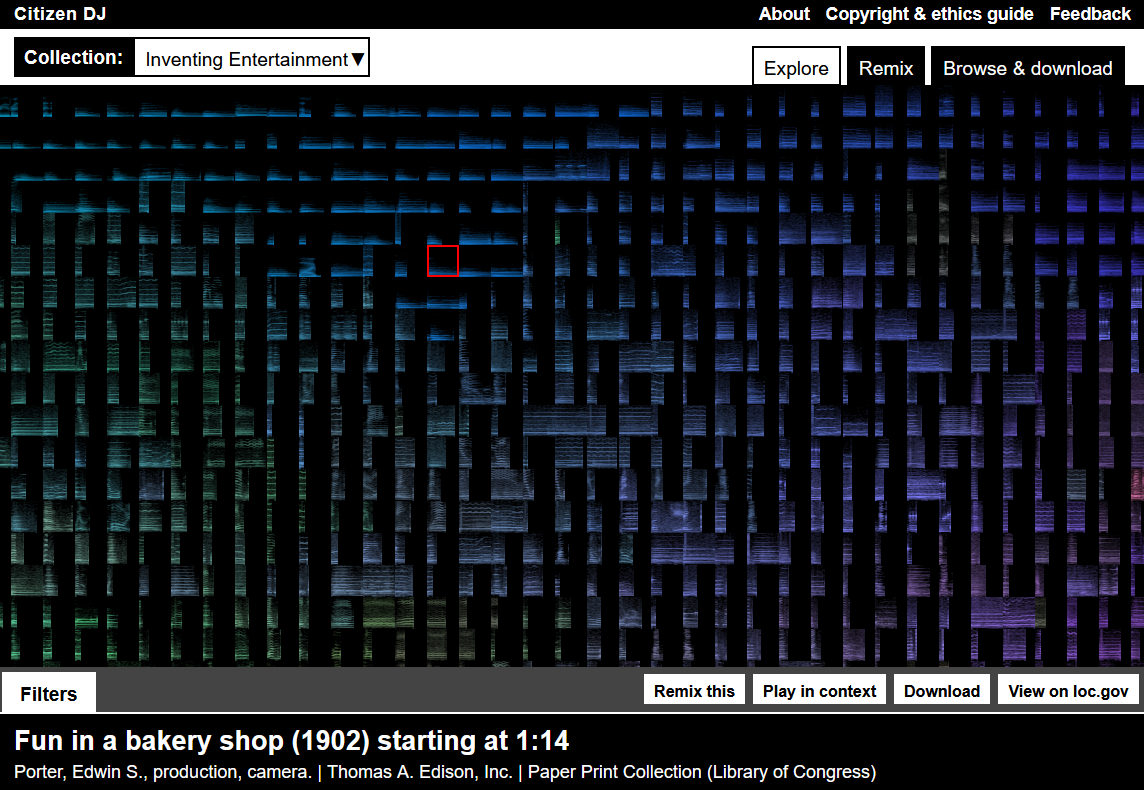

A screenshot of browsing thousands of audio clips in the Citizen DJ explore tool

A screenshot of browsing thousands of audio clips in the Citizen DJ explore tool

When a collection is composed of tens, hundreds, or even thousands of hours of audio, it becomes infeasible to listen to them all. The Library often uses words to describe what is contained in such a collection. Citizen DJ complements this by allowing patrons to use their ears to get a sense of what is in the collection sonically. This will give attributions of the audio that would often go missing in a written description: audio quality, timbre, color, or from the mindset of a producer, its “vibe.”

Once you find a sample you like, you can then click through to listen to the full audio in context from the Library’s main website. You can also jump into another interface that allows you to quickly get a sense of what this sample might sound like in a new hip hop track.

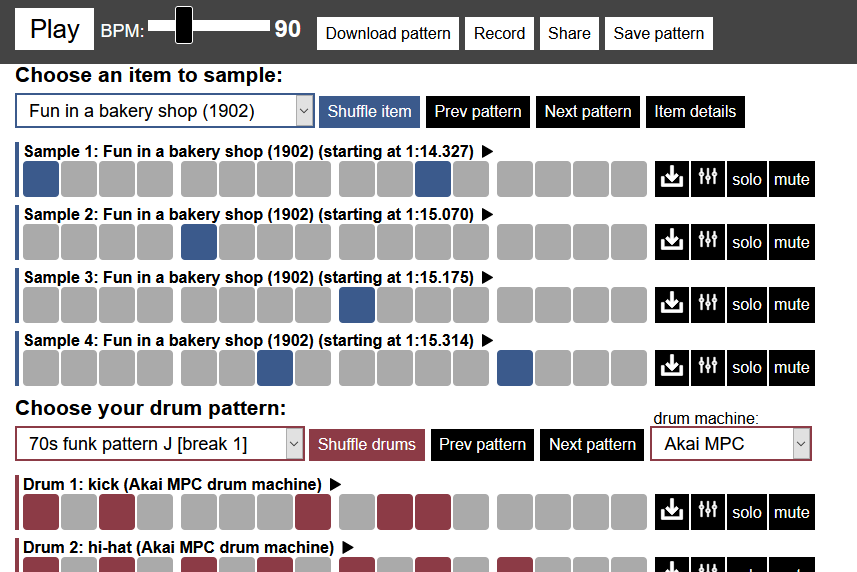

A screenshot of a looping music sequence the Citizen DJ remix tool

A screenshot of a looping music sequence the Citizen DJ remix tool

Hip hop producers would often take time to chop, loop, and transform snippets from source audio material as building blocks to create new music. Citizen DJ attempts to streamline this process by chopping up, looping, and adding beats to the samples for you right in the browser. You can very quickly randomize your samples, randomize your drum patterns, speed up, and edit the samples in real time.

But more importantly, I designed Citizen DJ to be as compatible as possible with existing music production workflows and software. Once you find a loop you like, you can download it as a wav file and import that into your favorite DAW. Similarly, you can download the raw source material as sample packs composed of thousands of audio clips that you can import, chop up, transform, and arrange yourself in your favorite music production software.

A screenshot of importing Citizen DJ samples into other music production software

A screenshot of importing Citizen DJ samples into other music production software

About midway through my residency, amidst the global pandemic, we launched a beta version of Citizen DJ to the public. In my post, I acknowledge the special impact the pandemic has on music professionals’ primary sources of income such as cancelled tours and concerts. At the same time, our collective reliance on music and other forms of art and entertainment is immeasurable. Even though we could not address the economic impacts to musicians directly, we hoped that we could open up Citizen DJ as a tool and resource to creatives across the country while they are stuck at home. We wanted to hear from them directly if these tools would be useful to them and if not, how could we make them so.

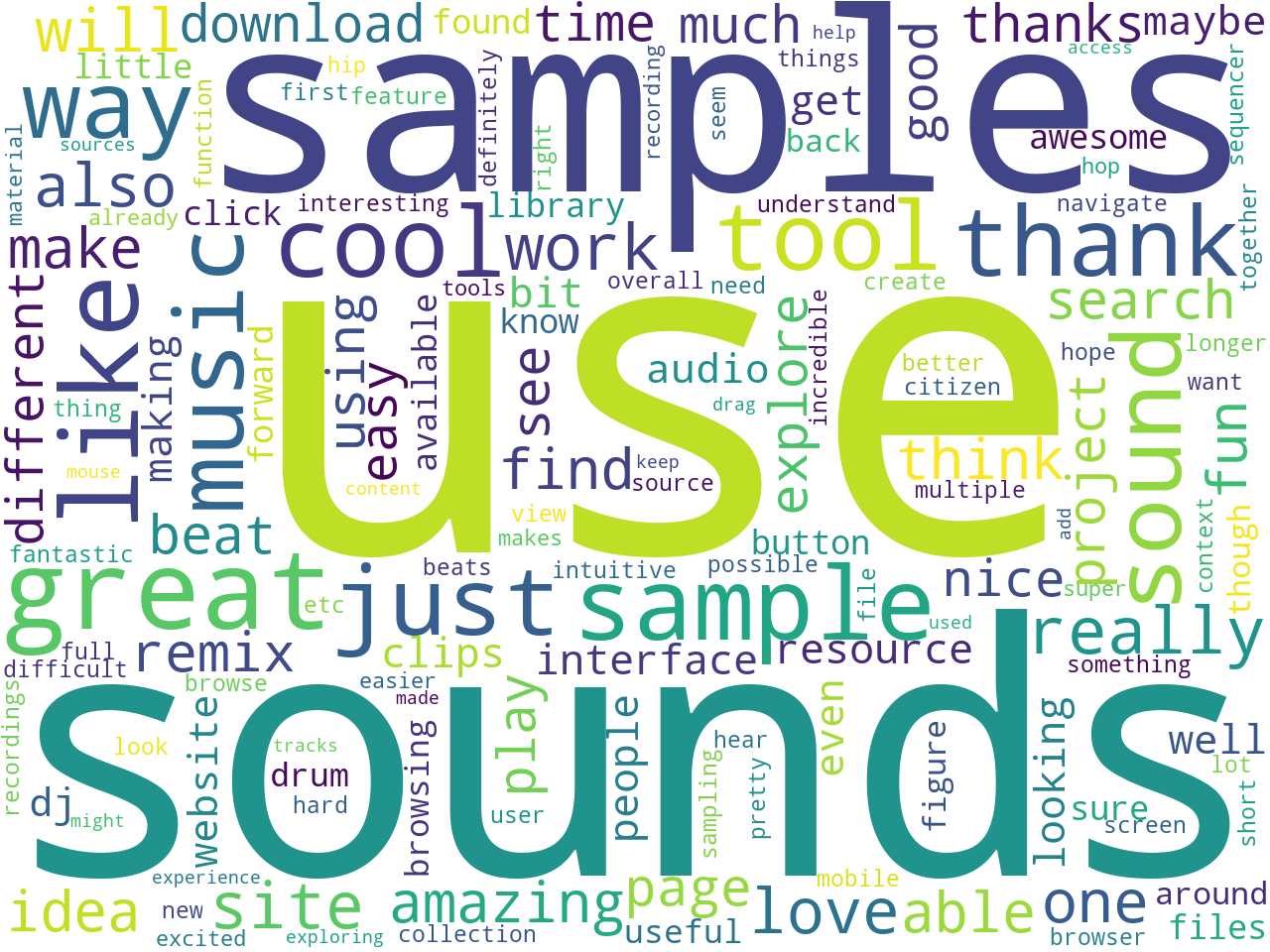

We were hoping to get feedback from a few hundred users, which would represent an unusually high number for a Library pilot project. The actual response was quite overwhelming. In just a couple weeks, we reached nearly a hundred thousand unique sessions and did not stop after that. What struck me in particular was the diversity of people, professionals, and organizations we reached–often those who have not previously engaged with the Library of Congress. We heard from amateur hip hop producers, professional musicians, filmmakers, educators, students, record labels, non-profits, well-known hip hop artists, and well-known non-hip hop artists. Over 80% of participants identified as artists or creative types while 91% agreed that Citizen DJ is for “people like me.”

In addition to structured feedback, we received thousands of comments, messages, and emails that contained questions, suggestions, frustrations, and commendations. While I was very excited and appreciative of the positive feedback, I was much more curious about the mixed to negative feedback we received. It is impossible to unpack these all in a single post, but the feedback could loosely be categorized into: interface bugs, compatibility issues, interface usability, feature requests, and clarity on copyright and usage.

Word cloud of the most frequent individual words in Citizen DJ user feedback

Word cloud of the most frequent individual words in Citizen DJ user feedback

As the sole developer, designer, and product owner for the Citizen DJ interface (with the overwhelming support from the Library’s UX team), it was quite challenging to decide what to work on during the remainder of my residency. My first priority was to make sure Citizen DJ was usable by as many people as possible, so my first round of work addressed many of the technical issues related to device compatibility, interface usability, and DAW compatibility.

Next, I focused on feature requests. The mixed and negative feedback I received from users were less about bad experiences, but more about how they want more features, especially music production features. To me, this was a good sign. These users clearly understood the vision and now want to integrate it into their own creative workflows. The challenge here was finding the right balance between the popularity of the feature requests, the effort involved in implementing those features, and how well those features align with the goals of the interface and project. Many of the requests were features of music production software, e.g. a swing function, custom sounds, mixing different clips together. However, the primary focus of Citizen DJ is around discovery and access of sounds for music making, so rather than focusing on music production features, I focused on making sure it was easy as possible to find sounds that you can use in popular music production software like Ableton and Fruity Loops.

For those interested in some highlights, here are some specific improvements I made in response to the feedback. You can now:

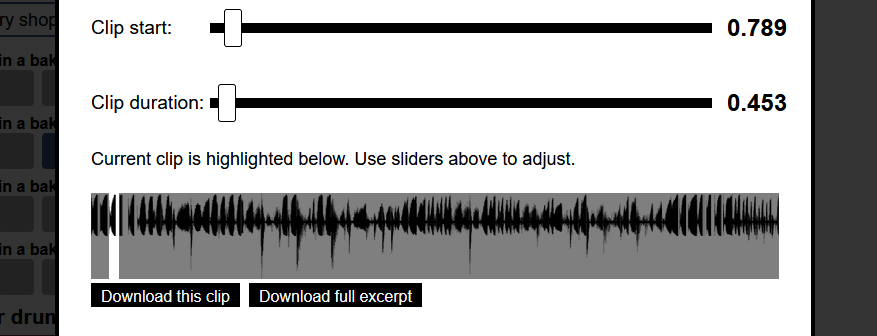

- change the size and location of an audio sample (this was one of our biggest requests)

- add additional drum tracks

- save a pattern that you made directly in the browser

- export your current pattern as a seamless .wav file loop

- download any clip your hear as a .wav file

- use the interface on a mobile device

- use the interface with a screen reader

- get more information about why a particular item is free-to-use

A screenshot of the new feature that allows users to customize the size and location of a sample

A screenshot of the new feature that allows users to customize the size and location of a sample

I continue to leave our feedback channels open, and you can always take a look at what issues and requests have been raised by visiting the project’s Github.

New beats

When thinking about how we wanted to launch Citizen DJ, rather than focusing on the collections or the tools, we thought it would be more meaningful to foreground new works that were created using those collections and tools. We also would use this as an opportunity to go deeper into understanding how people use Citizen DJ and listen to the music and dialogue that arise while engaging with the Library’s collections in this new way.

We had the pleasure to collaborate with non-profit organizations from across the country who have been using hip hop to engage with students and creatives of all ages on a variety of topics ranging from history, identity, social justice, and creativity. Organizations included Class Act Detroit, PATH (Preserving, Archiving, and Teaching Hip Hop) in Miami and Solidarity Studios in Chicago. Working with these organizations were illuminating, inspiring, and critical to fully realize the potential of Citizen DJ.

A screenshot of the virtual workshop with PATH. Photo courtesy of PATH.

A screenshot of the virtual workshop with PATH. Photo courtesy of PATH.

We collaborated on interactive online workshops that mixed conversations about Library collections and hip hop history with live demonstrations, performances, and beat battles. We also collected dozens of new tracks created by participants using Citizen DJ and Library collections. What better way to feature this new work than with a DJ and a turntable? And who better to take this on than the renowned DJ, Kid Koala, who truly embodies the spirit of this project in his innovative and surprising use of samples and diverse references from Vaudeville to blues, and rock to hip hop. In addition to a long and eclectic solo career, he has scratched for genre-bending groups like the Gorillaz and Deltron 3030 and has toured with the likes of Tribe Called Quest, the Beastie Boys, and DJ Shadow. For Citizen DJ, he produced what he calls an “Intercity beat tape”, jumping between time zones, bpms, and genres. This 20-minute megamix featured dozens of new tracks created on Citizen DJ by creatives from across the country that were featured in this year’s National Book Festival, marking the end of my residency and the pinnacle of this project.

Kid Koala on the ones and twos. Photo courtesy of Kid Koala.

Kid Koala on the ones and twos. Photo courtesy of Kid Koala.

And speaking of new work, I will finally mention that I had the pleasure to produce an album of my own using Citizen DJ called Some Tracks from the Stacks. This was an extremely fun experience which gave me first hand experience in using the tools that were developed for this project. I decided to build this album from a single collection rather than multiple ones because I wanted to consistently evoke the atmosphere and aesthetics of a specific era. I thought it was meaningful to reference this collection of Edison recordings because it has been about a century since their creation. My hope is that listening to the new tracks will encourage you to listen to the referenced recordings new ways (and vice versa).

The future

One thing I learned from the overwhelming feedback from Citizen DJ users: the sample is not just a relic of the past that kids of the 80s and 90s are nostalgic for. Despite the copyright challenges of sampling and the increasing ease of producing synthesized sounds, creatives young and old understand the excitement of finding, chopping, and flipping an existing sound into something entirely new. The sample is not dead.

What’s next for Citizen DJ? There are many unknowns, but there are also some knowns. The first thing that is known is that the underlying technology and interface of Citizen DJ are open source, meaning other institutions, organizations, or even individuals with enough software development experience can use Citizen DJ technology for their own audio collections. If you are someone who might fall into one of these categories, please let us know at LC-Labs@loc.gov! Our hope is that the development of this software is just the first step of many in opening up audio and video collections from all over the world.

The second known is that on January 1st 2022, over 10,000 sound recordings from the Library’s collections will enter the public domain due to copyright expiration as a result of the Music Modernization Act of 2018. The majority of recordings are part of the Library’s National Jukebox collection which has more than 10,000 acoustical recordings made by the Victor Talking Machine Company between 1901 and 1925 and are now owned by Sony Music Entertainment. The collection contains a mixture of popular music of that era (blues, ragtime, jazz, folk) and spoken word such as comedic skits, speeches, and readings. To get a sense of how much material this is, it would take approximately 20 continuous days to listen to the Jukebox material that will be available to use and reuse in 2022. Check back on Citizen DJ in 2022 to remix this material and in the meantime, feel free to browse and stream these recordings and imagine what new work you can make once they become free to use and reuse.

Beyond that, I hope Citizen DJ can represent just one of many technologies in the long line of innovations that has pushed hip hop into new and exciting spaces throughout the decades. I hope it inspires younger generations to ask what their Library, the Library of Congress, has that speaks to them. I hope that they can make new work that would be otherwise impossible or improbable. And I hope that this project sparks conversations about the role of the remix and the sample as critical artforms and tools for self expression and historical interrogation.